Today on Renaissance Wednesday we’re going to continue our tour of The Sistine Chapel focusing on Michelangelo’s masterpiece ‘The Last Judgment.’

The Last Judgment is one of the most popular themes in Christian art and often found in churches, usually at the church entrance as a reminder of the need for penance and faith before receiving communion.

In the Sistine Chapel, The Last Judgment is on the far wall over the altar.

The Last Judgment (begun in 1536) is strikingly different in tone to Michelangelo’s earlier Sistine Chapel frescoes. While the subject is meant to be somber, you find a weight of deeper sorrow that say Michelangelo’s Fall of Man fresco. This shift in tone and artistic style from High Renaissance to a period called Mannerism (late Renaissance to pre-Baroque) comes much from the tragic sack of Rome in 1527.

- Mannerism revolted against the perfect clean lines of High Renaissance art and exact form of the human figure – allowing from some exaggeration. You see Michelangelo’s shift to mannerism in The Last Judgment with it’s somewhat agitated composition, formless and indeterminate space, and in the tortured poses and exaggerated musculature of its bunches of nude figures

The Renaissance in Rome had filled the city with a sense of hope and wonder and the call of humanity to reach the heights, but The Sack of Rome destroyed much of the city and many were killed. This was not at the hands of a ‘barbarian’ outside attacker, but the forces of a Christian leader, Charles V of Spain. While Charles V did not intend for the sack to occur…this led to a period of mourning in Rome…many artists left for Venice and other cities.

Add in the beginnings of The Protestant Revolution, which left once staunch Catholic ally, Henry VIII of England leaving the church to create his own Church of England to the many other Protestantism movements in Germany and beyond.

- Interesting history: Clement VII refused to grant Henry VIII’s divorce to Catherine of Aragon at a time when the pope himself was essentially held captive in decision making by Catherine’s nephew Charles V. Pope Clement VII feared Charles would sack Rome again if he went against his authority in matters of state like granting a papal dispensation for divorce to Charles’s aunt. More info here.

The Renaissance ended with The Sack of Rome in 1527, but eventually things turned around in the subsequent decades. Given the turmoil of this time, you can feel the weight of time and age on Michelangelo’s spirit – his faith not shaken, but the optimism of his earlier work darkened by the realities of ‘the fallen world.’

Spirit + Art: The placement of The Last Judgment above the altar is deeply symbolic for the faithful, as many Christians believe they are fully united physically and spiritually with Christ when they receive communion. In Catholicism, The Mass itself is the highest form of prayer, where heaven and earth are united through the redemption of Christ. Catholics believe that the bread and wine becomes the body and blood of Christ. Learn more here.

- How this image speaks to me: We see the number of figures who are being judged as damned, but by placing this above the altar, where Christ is fully present in the Eucharist (communion) it is also a reminder not of judgment as much of grace. Those who are being judged here seem to have avoided the gift of grace and redemption (friendship with God) right before them, which is fully present in the Eucharistic meal/God’s constant presence in the lives of all humanity. As I contemplated this from the lens of faith and the juxtaposition of the altar and painting, it reminds all sinners that they can be redeemed, but they need to turn towards God’s grace.

Quick Facts about Michelangelo’s Last Judgment:

- The Last Judgment is massive in scope at 45 x 40 feet. In person in feels as though heaven has opened up and you are part of humanity below, looking up to Christ and the Saints. This no doubt was intentional to strike a chord and remind the faithful to seek God while he can still be found.

- There are over 300 figures in the painting including some mythological elements used for symbolic purposes (i.e. Minos in the underworld)

- The fresco was completed twenty-five years after Michelangelo’s original Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes. The Last Judgment fresco took four years to complete between 1536-1541; At the time of completion, Michelangelo was almost 67 years old when it was finished.

- The fresco was originally commissioned by Pope Clement VII before his death in 1534, but Michelangelo did not begin work on The Last Judgment until Pope Paul III took office.

- Fun fact: Clement VII was the nephew of Lorenzo de Medici and son of Giuliano de Medici who was sadly murdered in the Pazzi Conspiracy. Pope Clement and Pope Paull III both were facing a massive upheaval in the church with The Protestant Reformation and the need for a counter-Catholic Reformation. The Last Judgment was part of this focus to reform the church from within, while reaffirming the authority of the church doctrine for the faithful.

How to view The Last Judgment:

The Last Judgment is divided into several sections, which all connected to the coming Last Judgment at the end of time, which is referenced in Revelations.

- The central figure of the painting is Christ, who is shown as a powerful and fair judge. He is judging with firm conviction not from bias or revenge, but rather as one with authority and understanding of each human soul.

- Michelangelo modeled his figure of Christ on a statue of Apollo, not to equate Christ with the pagan god, but rather to show the form of perfection, which the Apollo statue revealed to the sculptor.

- Mary is on his right (our left) and is sorrowful because in the last judgment she can no longer intercede for even the worst of sinners to be redeemed by her son.

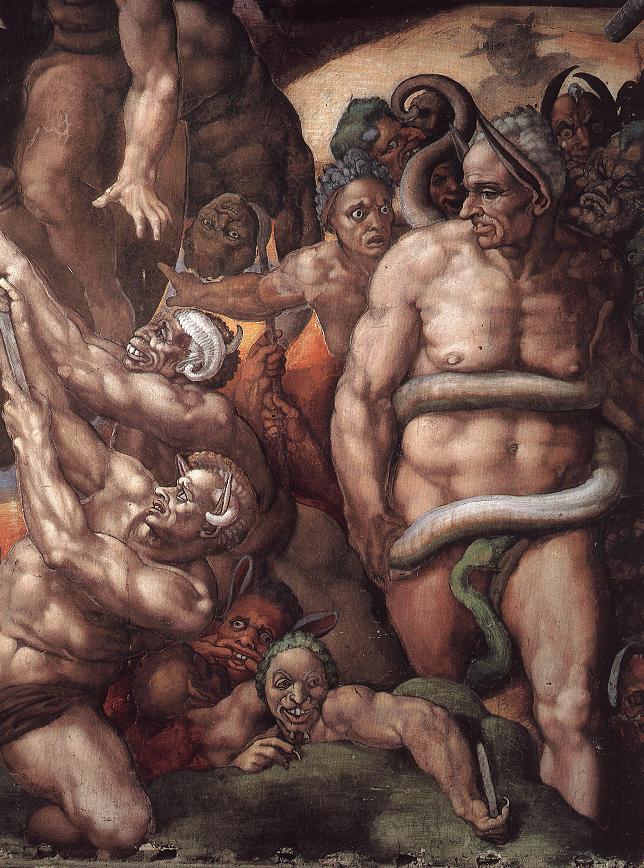

Right hand corner (if you fact painting): The Damned:

- Those who are damned here therefore are people who repeatedly rejected calls to grace. Many of the damned are being carried off into the realm of hell, but for all their suffering they seem in their space. One exception to this is a sorrowful figure who is obviously regretting his life decisions and seems to be moving near the saints, but is trapped in the realm of the damned. While this image strikes each viewer uniquely to me it is the highlight of the painting. I see it as a call to action to pray and intercede and ‘pray for our enemies,’ and reach out to the desperate.

- I think we can all identify with this figure as we have all fallen short of the glory of God and made mistakes…the call to action is how we learn from those mistakes when we fall down…do we pivot back to God and our call to love one another or do we wallow in the shame of falling down?

- Michelangelo was not one to mince his paints when he wanted to get a message across…The figure of Minos – a demon of the underworld with a snake encircling him and horns is actually a depiction of the pope’s Master of Ceremonies Biagio da Cesena.

- Biagio detested Michelangelo’s use of mostly nude figures in the original version of The Last Judgment. Art historian Vasari quotes Biagio as stating: “it was most disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully, and that it was o work for a papal chapel but rather the public baths and taverns.

- Michelangelo made fun of Biagio’s ‘judgment’ of his work by making him out as Minos, the mythological judge of the underworld. He covers him with a snake, which was condemnation in itself. He also put donkey horns on Biagio as a sign of foolishness.

- When revealed, the majority of Cardinals and faithful were overwhelmed by the beauty of the painting and had a laugh in recognizing their colleague. Biagio complained, but the pope understood the humor and dismissed Biagio’s anger.

- However in the end Biagio won…eventually after Michelangelo’s death, the nude figures were lightly covered by Michelangelo’s friend and peer Daniele da Volterra. Nicknamed ‘Il Braghettone,’ meaning the breeches maker, Daniele kept the revisions at a minimum as he greatly admired Michelangelo.

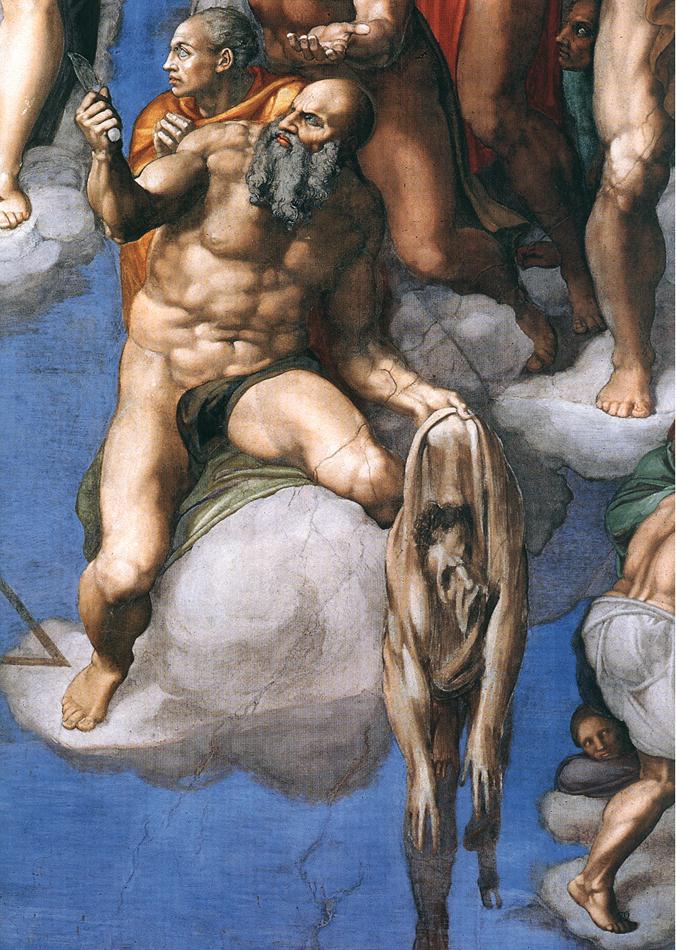

The Saints:

On the right and left side of Christ you’ll find an array of saints, some identifiable and others elusive. St. Peter offers his keys to Christ both as a reminder of his service to Christ, but more importantly because they keys are no longer needed after The Last Judgment where all of the faithful for all time will be fully admitted into the kingdom.

On the flayed skin of St. Bartholomew, you’ll find a self portrait of Michelangelo. In one of the personal poems Michelangelo wrote, he used the metaphor of a snake shedding its old skin for hope for a new life after death. This is perhaps his own artistic prayer for redemption and reminder of his ‘gift of art’ to God’s service.

The Saved:

On the bottom left, moving to the top of the painting, angels carry the souls of the saved to heaven. Unlike some portraits where the angels gracefully move figures with seemingly no effort, Michelangelo shows the effort of moving the saved to heaven. The gift of salvation was no easy feat, it came from the death of Christ on the cross, and even for the saved, there is the reminder of the grace and effort in that gift from God.

Resources:

- Khan Academy has a great study guide on The Last Judgment here

- I recommend Dr. Kloss’s Great Courses series on The Italian Renaissance, which features an in-depth series of lectures on The Last Judgment and Sistine Chapel.

Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE for more art history and art adventures.

Art Expeditions is written by art history lover and travel enthusiast Adele Lassiter.