In early March I made a pilgrimage to the phenomenal Philadelphia Museum of Art, where I was able to travel through over 2000 years of art history, standing face to face with masterpieces by the likes of Duccio to Fra Angelico, Judith Leyster to Monet, Cezanne to Van Gogh and Picasso to Warhol. The Philadelphia Museum of Art has a diverse collection of works in a variety of time periods in styles, which truly allow guests to go on an art expedition from Asia to Europe, and also learn about prominent Philadelphia artists like The Peale Family.

In the coming weeks, Art Expeditions will explore the rich holdings of The Philadelphia Museum of Art. We’ll be examining key works and the influential artists and art movements behind them.

*Check out my recent blog about my visit to The Philadelphia Museum of Art on our sister blog American Nomad Traveler This blog details my visit to the museum and best tips to enhance your tour.

Let’s kick off our Art Expedition trip to the Philadelphia Museum of Art with a sampling of Must-See artworks from the permanent collection.

Medieval Wonders:

The Philadelphia Museum of Art boasts a wonderful collection of Medieval and Gothic art, including several pieces from the famed Sienese school of art.

One of the museum’s crown jewels is Duccio’s Archangel, a panel once part of his famed Maesta, which mostly still hangs in Siena today. Portions were disassembled and removed in 1771 ,eventually being sold to D.C.’s National Gallery and The Frick in New York and PMA. Maesta is a term referring to a depiction of The Virgin Mary in a heavenly court. The work is done in egg tempera. You can identify the subject as an archangel by the wand in his hand. In art, the wands symbolize the angels’ work to expel satan from heaven.

Who was Duccio?

Duccio is considered one of the greatest Italian painters of the Medieval era and the founder of the Sienese school of art. He masterfully blended Byzantine and Gothic Styles inspired by sculpture of Pisano and also French Gothic Metal Work. His innovative use of color,line and pattern, helped depict space and provided a deeper human emotion in his paintings…thus setting the stage for The Renaissance. Some scholars believe that Duccio was trained by Cimabue or at least influenced by him. He ran a large workshop and helped shape generations of Sienese artists, who later influenced Florentine art. Sadly Duccio died in 1319, most likely from the terrible Black Death that decimated the city’s population.

The Black Death devastated Siena and while it is a beautiful and thriving city today, it is interesting to note that the population of Siena prior to the Black Death was around 50,000 people, the same approximate population as today. After the plague the city continued to be an important city, but it’s growth and cultural movements shifted to Florence. This article from Montana State does a good job showing the impact of the plague in Siena.

Another Sienese painter featured in the PMA is Pietro Lorezetti, who we featured in our recent Unlocking The Easter Story through Art blog post.

A contemporary of Duccio, Pietro Lorenzetti and his brother Ambrogio were renowned Sienese painters who introduced naturalism into Sienese painting. This work, The Virgin and Child Enthroned with a Servite Friar and Angels was completed in 1319. It once formed the center section of a large altarpiece. The small man kneeling in prayer wears the robe and tonsure haircut of a monk or friar. It is believed he is the donor who commissioned the altarpiece probably for the church of his own convent. (source PMA)

If you are interested in learning more about Sienese art…

- The National Gallery in London is still hosting their exhibit on Siena 1300-1350 – The Rise of Painting through June 2025 and have a number of resources about Sienese art and the exhibition on their website.

- You may also enjoy this book – Sienese Painting The Art of a City – Republic

- SmartHistory has a wonderful summary of Sienese Art and how it was interconnected with culture and government.

Philadelphia Museum of Art transports visitors back in time to Medieval France, where they can walk through semi-reconstructed French Abbeys from The Romanesque and Gothic eras.

The cloister from the Abbey of Saint-Genis-des-Fontaines, which was brought over stone by stone from France. A cloister is a covered walkway, typically found in monasteries/abbeys that provide spaces for contemplation and reflection.

At Saint-Genis-des-Fontaines, the outer walkway held doors that opened into the dining hall, the chapter house (where the abbey was administered), and the church. In addition to functioning as a connecting space, the courtyard and its colonnade were used by the religious community for processions, services, and communal readings. The cloister also provided an area where individual monks could engage in private prayer and contemplation. (source)

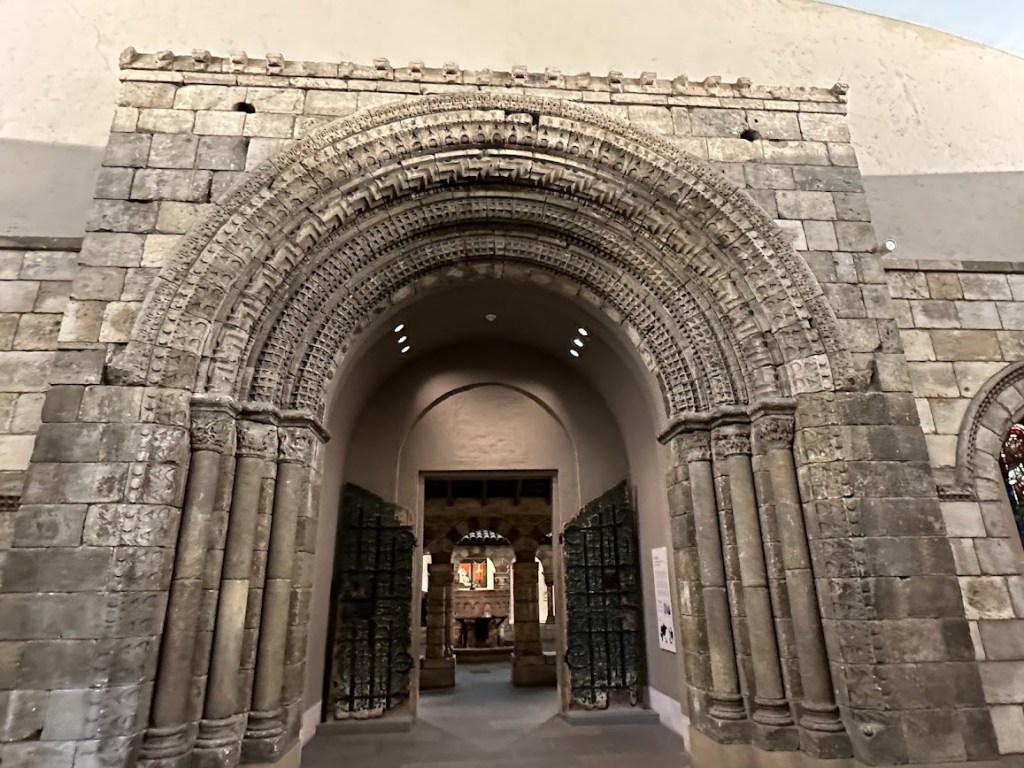

This Romanesque portal, originally the main entrance of the small French Augustinian abbey church of Saint-Laurent (a pilgrimage stop on the way to Santiago de Compostela), showcases bold abstract patterns and detailed capitals with intertwined branches, leaves, and birds. Its style is linked to the influential Cluny monastery. When installed in the Museum at the suggestion of George Grey Barnard, two smaller, regionally-inspired but unprovenanced doorways were added. The portal is now displayed opposite a group of Romanesque capitals, including some from Saint-Laurent itself.

(French Gothic Portal / Arcade Limoges)

A silent witness to centuries, this archway once linked the contemplative cloister and the communal chapter house of the Convent of Les Grands Carmes des Arènes in Limoges. This Carmelite monastery, established in the 1200s upon the foundations of an ancient Roman arena and continually expanded, utilized the region’s characteristic basalt for its construction. The French Revolution brought an end to the convent’s long occupation (1789–99), leading to its closure, the expulsion of the nuns, and the demolition of much of the complex. Remarkably, the chapter house, and with it this arch, survived to be rediscovered in the early 20th century, eventually leading to its preservation in this museum.

Renaissance Art

~

The resplendent wonders of The Renaissance are on full-display at The Philadelphia Museum of Art. We’ll be doing a deep dive into the museum’s Renaissance collection soon. Today we’ll zero in on two important Renaissance works.

Philadelphia is fortunate to possess a double-sided painting by Masaccio, a pivotal figure often hailed as the first Renaissance painter and a father of this transformative artistic period. The artwork features depictions of Saints Peter and Paul on one side, and John the Evangelist and Martin of Tours on the other.

Masaccio revolutionized painting through his pioneering discovery and application of linear perspective. This technique, now fundamental, was groundbreaking in its time, enabling artists to achieve unprecedented realism and depth in their compositions.

This particular painting was originally part of a double-sided altarpiece located in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. Art historians believe that the great master Masaccio conceived and began painting this panel before his untimely death at the young age of 27. It is thought that his collaborator, Masolino, completed the work.

Having such a piece in Philadelphia offers a direct connection to the very origins of the Renaissance and the innovative techniques that defined it.

This small but masterful work by Tuscan painter Fra Angelico showcases his vivid use of color and perspective to bring to life the story of Mary’s being laid to rest. As a Dominican friar, with a deep piety, used his talent for art to bring the scriptures to life in a meaningful way. He was an innovator in realism, impression of volume and linear perspective to define figures and space.

Many of Fra Angelico’s works can be found in situ at The Convent of San Marco in Florence where he lived and painted.

Fun fact – did you know that Fra Angelico is now known as Blessed Angelico – as he is on the road to being canonized as a saint.

Rogier van Weyden

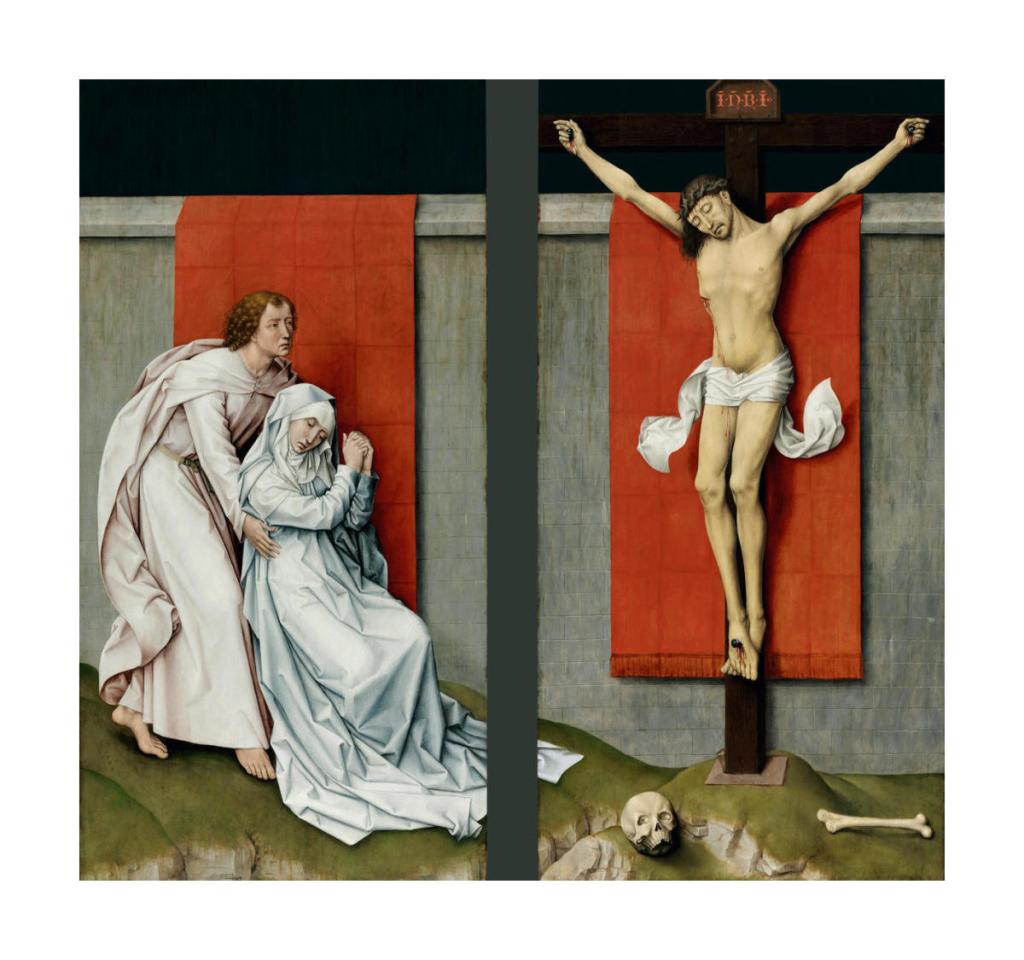

The museum also features a wonderful collection of Northern Renaissance art including Netherlandish master Rogier Van Weyden’s Crucifixion diptych depicting The Crucifixion. Weyden’s distinctive style, characterized by his attention to detail while also capturing the raw emotions of the characters in his works instantly draws you in.

From the museum website: “To convey overwhelming depths of human emotion, Rogier located monumental forms in a shallow, austere, nocturnal space accented only by brilliant red hangings. He focused on the experience of the Virgin, her unbearable grief expressed by her swooning into the arms of John the Evangelist. The intensity of her anguish is echoed in the agitated, fluttering loincloth that moves around Christ’s motionless body as if the air itself were astir with sorrow. Rogier’s use of two panels in a diptych, rather than the more usual three found in a triptych, is rare in paintings of this period, and allowed the artist to balance the human despair at the darkest hour of the Christian faith against the promise of redemption.”

The intensity of this painting makes you both uncomfortable while also drawing you closer to Christ, Mary and John. You want to console Mary and John. As a person of faith, even though I know the sacrifice of the cross and of hope of the Resurrection, it still is hard to digest the suffering and human element. Weyden captures this sorrow and sadness beautifully.

A diptych is a painting, often an altarpiece, consisting of two hinged wooden panels that can be closed like a book. Small diptychs and triptychs (three-paneled works) were common in private households, allowing individuals to carry them for personal prayer and close them when needed. In contrast, churches began to adopt larger-scale paneled pieces, such as Weyden’s crucifixion. Occasionally, specific panels within these larger works would only be displayed during particular times of the liturgical year.

Impressionism:

We’ll fast forward a few hundred years to post 1850 France, when new movements in art from Romanticism to The Barbizon School and eventually Impressionism emerged.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art can boast of having one of the best collections of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art in the United States and beyond. The large interconnected galleries feature a flurry of fabulous works by Monet, Manet, Morisot, Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley, Cezanne, Van Gogh and more.

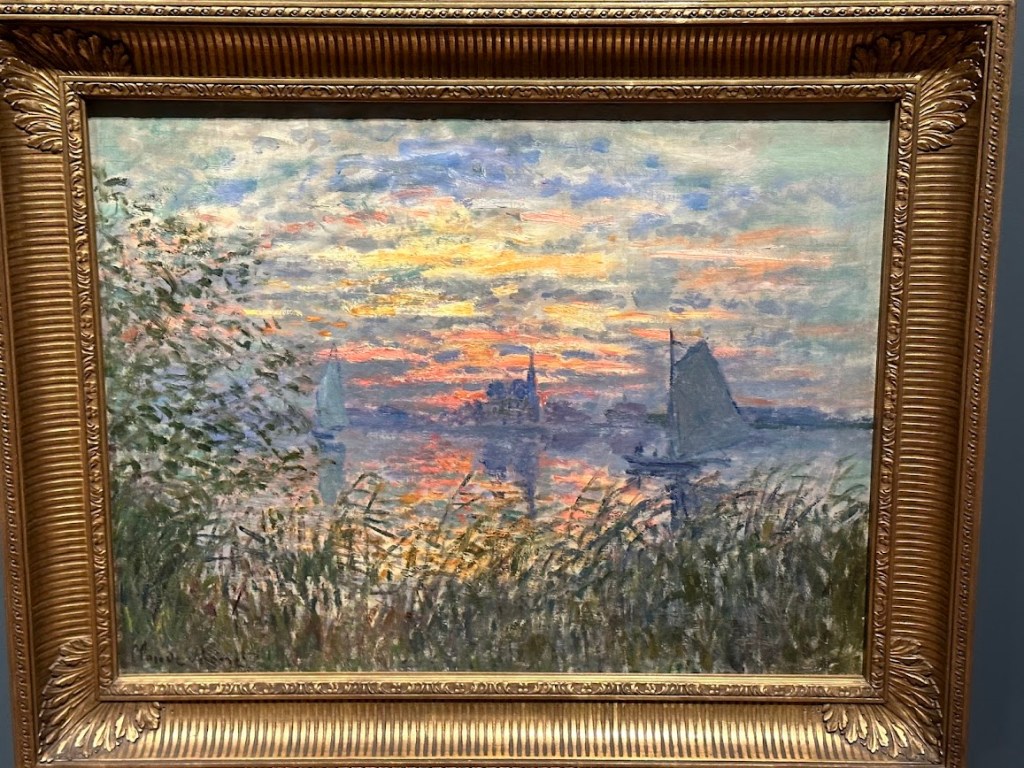

Like many art lovers, I’m drawn to French modern art from 1850 to 1950, not in opposition to earlier more traditional master works, which are beautiful, but rather the glorious use of color and that mix of realism with emotion that brings scenes to life. A Monet’s thick and rapid brushwork might not be realistic, but it captures the heart of how it feels to stare at a sunset. You can nearly feel the ocean waves crashing in a Boudin seascape.

A fascinating connection: the major Impressionist Mary Cassatt and the prominent American realist Thomas Eakins, known for his work including “The Gross Clinic,” both studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. While Cassatt later immersed herself in the European Impressionist movement, and Eakins also had ties to France, “The Gross Clinic” remains a significant work within American art history and is closely linked to Philadelphia’s art institutions.

Get ready! We’ve got lots of posts coming up about the museum’s amazing Impressionism and Post-Impressionism collection. To get you started, here are a few of my absolute favorites

Monet is in full bloom at the Philadelphia Museum of Art:

The PMA has several works by Edouard Manet – a precursor and Father of Impressionism. The seascape is a personal favorite, because it showcases Manet’s effortless ability to create a dynamic scene even with seemingly simple broad brushwork. Manet could paint anything, including detailed portraits and scenes, but he shines with even the simple landscapes. You can feel the water and the movement in this painting.

I love the bustling city scape in the Renoir below. The figures are not detailed, yet feel realistic as our eyes often capture crowds not with precision that fluid movement as passerby run to avoid traffic and the trees blow in the breeze. Renoir is a favorite colorist of mine and I love his use of color in this work.

Cezanne is one of my favorite artists. Every since I first saw one of his Mount St. Victoire interpretations at age nine, I was inspired by his use of color and shape. My sweet tabby cat is named Cezanne in his honor.

Cezanne is known as the Father of Modern Art because he broke boundaries with his use of form and line. Cezanne like to slowly study objects and look at them from different angles. He wanted to capture the way something made him feel, rather than only painting realistically. He also wasn’t afraid to deconstruct natural scenes into shapes and patterns, which inspired artists like Pablo Picasso as he ventured into Cubism.

Did you know: Between the extensive holdings of Cezanne’s works by both The PMA and Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia could be dubbed ‘Cezanne City. We’ll be deep diving into the PMA and Barnes Foundation’s Cezanne collections in the coming month.

Édouard Vuillard was a member of the Nabis group a loose collective of French artists active in the late 1880s and early 1890s. He, along with other Nabis like Pierre Bonnard and Maurice Denis, explored decorative art, interiors, and everyday life with bold colors and simplified forms.

Modern Art Movements

The Philadelphia Museum of Art has an extensive collection of modern art from Matisse and Picasso to Warhol and beyond. Stay posted for our PMA Modern Art feature.

In this post I wanted to share a few of the works in the modern week that spoke to me.

Early American Art

Given Philadelphia’s diverse culture and prominent role in the founding of the United States of America – it is no wonder that Philadelphia has long been a center for the arts. Early American artists like The Peale Family were movers and shakers in Philadelphia’s art scene. We’ll be focusing specifically on this wing in a future post.

Titian Ramsay Peale, who crafted natural science displays, gestures at the top of the stairs as his older brother, Raphaelle, an artist with his palette in hand, strides upward just above a real step attached to the base of the canvas. The life-size portrait is known to have startled and delighted visitors, reputedly even George Washington, before the Peale Museum’s collection was dismantled and finally sold in 1854. Acquired by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1945, the picture continues to engage and welcome visitors. – PMA website

I hope this ART Expedition got you excited for our upcoming series on The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE to the blog for all the latest art adventures.

Art Expeditions is written by artist and art-history lover Adele Lassiter. When she’s not painting and exploring art museums she also maintains our sister blog American Nomad Traveler and is a singer-songwriter whose album American Nomad is out now.

#philadelphiamuseumofart #cezanne #monet #fraangelico #artblog #arthistory

[…] Posted on May 7, 2025May 7, 2025 by ynpgal77 My Absolute Must-See Favorites at the Philadelphia Museum of Art […]

LikeLike